In a previous blog post, Why I Use oral Contrast for Abdominopelvic Imaging, I stated that I am a strong believer in the benefits of properly administered oral contrast for CT imaging. I believe that oral contrast both accentuates bowel pathology if it exists and helps to exclude pathology if it doesn’t exist. Non-distended, non-opacified loops of bowel may hide pathology that is present or may suggest a pathology that is not present.

But how do we define properly administered oral contrast? Ideally, I would like to see contrast filling every segment of the bowel from the stomach to the rectum. However, this is not easily achieved on a routine basis without administering greater than one liter of contrast. Therefore, for the routine patient, I usually strive to emphasize opacification of the bowel from the stomach to the mid-ascending colon. In order to achieve this goal, the timing of oral contrast administration in relation to the scan time is crucial. Scan too soon and the distal bowel is not yet opacified; scan too late and the contrast has already passed through the stomach and proximal jejunum.

In my practice, the average patient is in his 60s. Many of these patients come in with non-specific indications, such as abdominal pain or unintentional weight loss, which means that every organ system should be optimally opacified for best evaluation. Others present for evaluation of specific known entities but are then found to have unexpected pathology elsewhere within the abdomen. I have gathered some representative cases that demonstrate the benefits of good bowel opacification.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

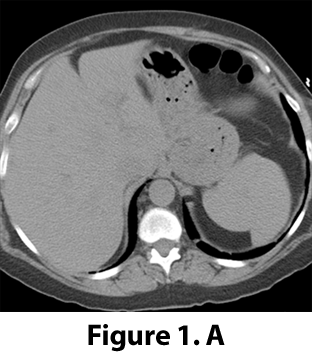

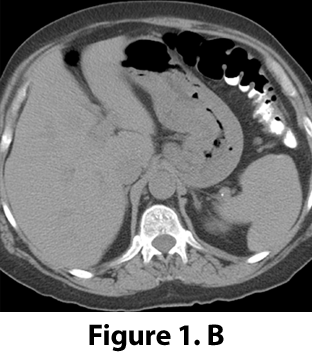

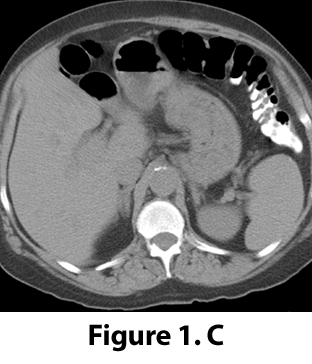

Figure 1. A–C: CT performed on a 67-year-old male for newly diagnosed prostate carcinoma. Study performed without IV contrast due to chronic renal insufficiency. Oral contrast was administered but had transited through the stomach and proximal jejunum prior to imaging. |

|

|

|

|

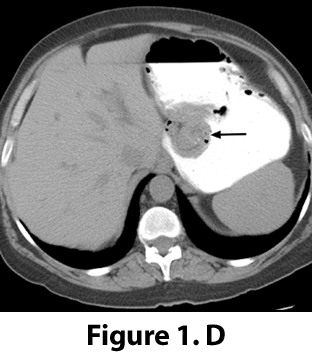

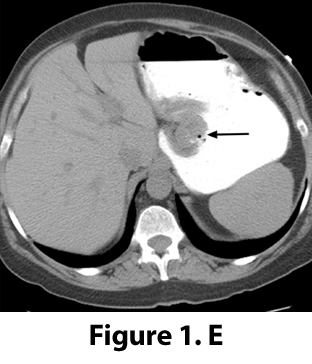

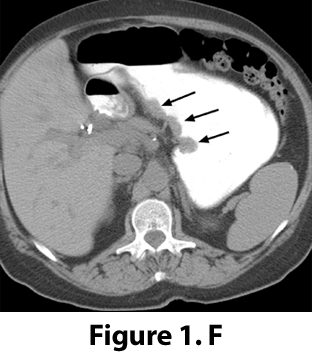

Figure 1. D–F: CT performed one month later with good gastric distension by oral contrast reveals an unsuspected polypoid gastric adenocarcinoma arising from the lesser curvature (arrows). |

|

|

|

Peter Quagliano, M.D.