The 3.5 million breast cancer survivors currently living in the United States lost a hero on October 16, 2019. A hero they probably never heard of, but to whom many owe their lives and, more importantly, the quality of their life after diagnosis.

In this age of breast cancer awareness campaigns and “save the tatas” bumper stickers, it’s hard to imagine that even as recent as the mid-1970’s, a diagnosis of breast cancer used to be talked about in hushed whispers as an almost certain death sentence. And if you were lucky enough to survive – every waking day would be a painful reminder of your disease.

Because at that time, the standard treatment for breast cancer was radical mastectomy- a procedure unchanged and unchallenged since the late 1890’s.

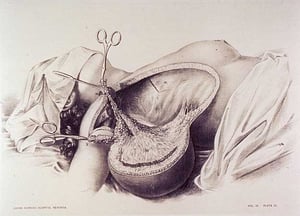

A brutal operation

Revolutionary in terms of 19th century medicine, this procedure involved removing the breast, the lymph nodes under the armpit, the chest muscle, and in some cases, even the ribs.

The prevailing theory then was that cancer cells in the breast always passed through the lymph nodes prior to metastatic spread and, therefore, required radical surgery to remove the entire breast, underlying chest muscle, and axillary lymph nodes to halt metastasis.

The prevailing theory then was that cancer cells in the breast always passed through the lymph nodes prior to metastatic spread and, therefore, required radical surgery to remove the entire breast, underlying chest muscle, and axillary lymph nodes to halt metastasis.

However, despite this extensive surgery, the survival rate past 5 years was only 40%. Many women died from their disease and it was theorized that this was because tumor cells were dislodged during the operation.

“Survivors” were left terribly scarred, disfigured, and weakened. They suffered from lymphedema (arms swollen with lymphatic fluid) as their lymph nodes had been removed. Removal of the chest muscle hampered their ability to move their arms. It was a miserable existence.

Clinical Trials – what a novel idea

In the spring of 1957, Dr. Bernard Fisher was invited to an NIH meeting to discuss with 22 other surgeons the establishment of the Surgical Adjuvant Chemotherapy Breast Project, later known as the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP)

The idea of using clinical trials to obtain information, and the idea of giving therapy following surgery, were novel approaches to treatment.

According to later interviews with Fisher, he was initially reluctant to relinquish his research on liver regeneration and transplantation to take up the study of breast cancer and other malignant diseases, but he became intrigued by the subject of tumor metastasis and "the new concept of the clinical trial."

He was also surprised at how little knowledge there was related to the biology of breast cancer and how little interest there was in understanding the disease.

He would spend the next 40 years studying breast cancer.

The heresy of less invasive surgery

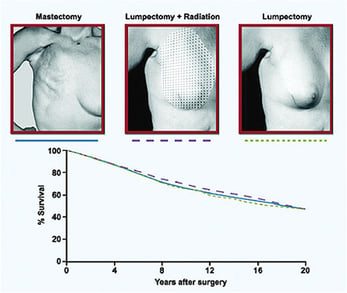

In 1971, Dr. Fisher led the NSABP in a landmark clinical trial in women with primary breast cancer comparing radical mastectomy with less extensive total mastectomy. In 1976, he initiated a study comparing total mastectomy with less disfiguring lumpectomy, with or without breast irradiation.

What he found was that there was no survival advantage in removing more tissue. Less invasive surgeries resulted in similar survival rates as the more extensive surgeries. These studies provided a scientific basis for less extensive surgery.

But of course, when something flies in the face of convention, it is usually met with hostility and distrust.

Dr. Fisher’s research was no different, and he was accused by his peers of endorsing methods that would put more women’s lives at risk.

Support from unexpected places

However, there was one group of people that embraced Dr. Fisher’s research: women’s rights activists. Fisher’s research was timed just right to coincide with the fight for women’s equality in the 1970’s.

According to an interview with Cynthia Pearson, Director of National Women’s Health Network, "The women's health movement began talking about mastectomy as one of the examples of sexism in medical care in the United States. It became, in a small way, a rallying cry."

As a result, Fisher's ideas became a political issue as well as a medical one.

A new understanding of how cancer spreads, a new way to combat it

For over 10 years, Dr. Fisher and his research team carried out "a multitude of investigations regarding the biology of tumor metastasis."

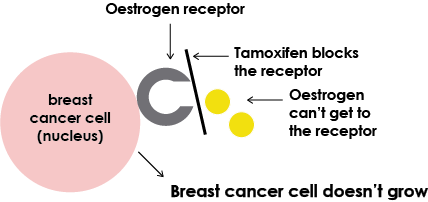

These studies showed that the addition of systemic, adjuvant chemotherapy or hormonal therapy provided a survival advantage over surgery alone and led to the first trial of tamoxifen as a breast cancer prevention agent in 1992.

That trial showed that tamoxifen decreased the incidence of breast cancer by half in women with increased risk for the disease. Millions have benefited from this discovery.

|

Through his work, Dr. Fisher revolutionized the treatment of breast cancer thanks to his systematic scientific approach. Because of his dedication, women diagnosed with breast cancer today are presented with treatment options that lead to longer, healthier, happier, lives.

His study of how breast cancer metastasizes provided insight into the biology of all cancers and we now take clinical trials for granted.

A legacy of survival

But perhaps his greatest legacy is that we also take for granted that a diagnosis of breast cancer is no longer an automatic death sentence or a disfiguring surgery with only an average of 4 in 10 women surviving past five years.

I suppose it was fitting that Dr. Fisher’s passing took place right in the middle of breast cancer awareness month. As they used to say in the ‘70s, “we’ve come a long way, baby” when it comes to the detection and treatment of breast cancer.

Thanks in large part to Dr. Fisher’s research, breast cancer is beatable as long as it is caught in its earliest stages. Today, an average of 9 in 10 women will survive past 5 years, 8.3 will survive past ten.

This is why women need to be their own advocates. We need to go for our annual mammograms beginning at age 40 and we need to embrace those heroes of today who are advocating for national dense breast legislation and insurance coverage of supplemental breast cancer screening for women with dense breasts.

Let’s not turn back the clock when it comes to our own breast health.

|

| Photo courtesy of NCI |

Related articles:

Mary Lang Pelton

Director of Marketing Communications